A doctor explains what we know about how the coronavirus is transmitted - and what we do not.

The spread of the coronavirus has been rapid and aggressive, leaving most of us thinking carefully about how we socialise with each other, how we clean surfaces and utensils, and wondering whether it is time to isolate ourselves from the outside world altogether.

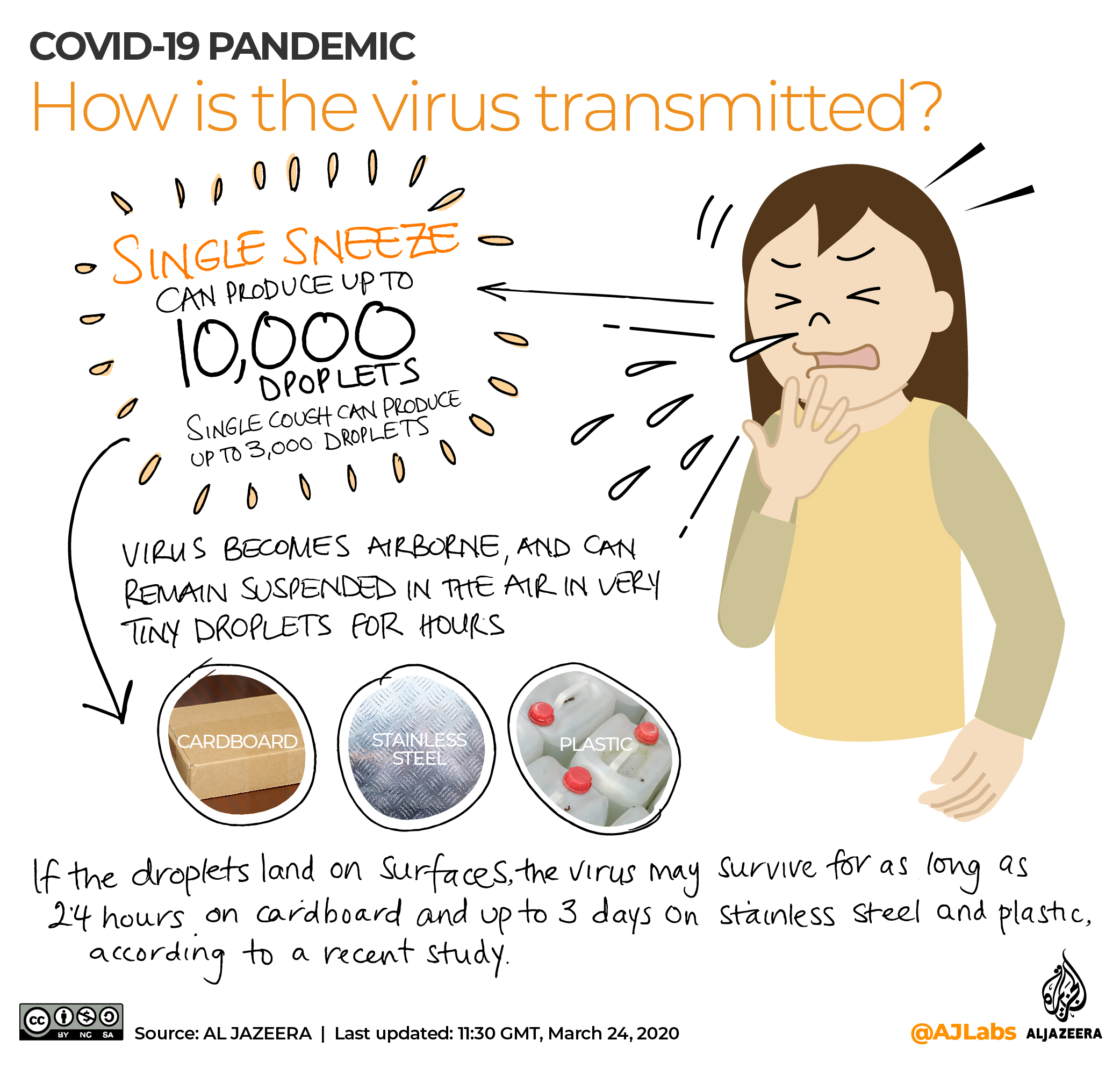

We know that the virus's main route of transmission from one person to another is through droplets which are sneezed or coughed out by infected people. A single cough can produce up to 3,000 droplets, while a sneeze can produce as many as 10,000.

These droplets then land in or are breathed into another person's airways, or fall on a surface that is touched by an uninfected person, who then touches their face - specifically their mouth, nose, ears or eyes.

This method of transmission is known as "droplet spread". While it is in these droplets, the coronavirus is only in the air for a short time and travels only a short distance before it is pulled down by gravity after being coughed or sneezed out.

The exact length of time the virus can "live" in the air outside of a host body is currently being researched. According to a recent report in the New England Journal of Medicine, some studies have put it at just a few seconds, while one suggests it may be two to three hours.

However long the virus can last, while it is in the air in droplets, anyone within two metres of the cough or sneeze can breathe it in and become infected. An uninterrupted droplet from a sneeze can travel around 60 metres, but most are caught in tissues.

The virus may also remain airborne in much tinier droplets, according to some emerging evidence published in the same journal this week by scientists at Princeton University, University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) and the US research agency, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) - though not in significant quantities.

It is important to remember that these studies are only preliminary and other research has contradicted them, but if correct, this might explain why so many people are becoming infected so quickly.

When a virus becomes airborne, it is described as an "aerosol". This means the virus remains suspended in the air in very tiny water droplets - smaller than the ones coughed or sneezed - long after larger droplets have fallen to surfaces or been breathed in.

These tiny droplets can remain in the air for hours if the conditions are right - reduced air flow, open space and the right temperature.

When we think of airborne viruses, the one that most doctors will quote is measles. When a person infected with measles coughs or sneezes, the virus can remain suspended in the air in tiny particles for two hours, awaiting its next victim who will catch it by breathing it in.

The evidence we have that the coronavirus behaves in the same way as this is very patchy. It appears to have some aerosol qualities when tested under laboratory conditions only.

"Real-world" studies of how the virus behaves in the air, undertaken in hospital rooms where infected patients have been present, have so far proved negative. However, scientists are keen to emphasise that more work is needed before coming to any definite conclusions.

It is far more urgent to focus on how we do know it is spread.

As well as catching it via droplets, another major route to infection is from surfaces on which the virus has landed. It is only now becoming clear how long the virus can stay on surfaces if they are not cleaned regularly.

Coronaviruses are known to be especially resilient in terms of where and how long they can survive without a human host.

A study published last week by the NIH showed that under ideal conditions, the virus could survive on cardboard for up to 24 hours and up to three days on plastic and stainless steel.

The main reason it survives longer on surfaces than in air is simply that it drops down from the air because of gravity, so physically does not stay in the air for long.

When the virus is sitting on these surfaces, it only has to be touched by a person with their hands. When they then touch their mouth, nose, eyes or ears, it can find a way into their airways and another infection begins.

It is, therefore, vital to clean household surfaces with disinfectant containing 60 percent to 70 percent alcohol, or with household bleach.

It is harder to know how long the virus can survive on clothing, but the NIH states that it is less likely to last as long on porous or fibrous material, though the organisation is currently running follow-up experiments to find out for sure.

Another route of transmission that is becoming known is the faecal route. There is increasing evidence to suggest the virus can penetrate the gastrointestinal tract by travelling through the body, and then be excreted through faeces. It is not believed to be a major route of transmission, but adds to the mounting reasons as to why you should wash your hands after using the toilet.

Much is yet to be learned about this new virus, but every way it is spread can be fought through appropriate hygiene measures. Handwashing and disinfecting surfaces remain the best weapons in our arsenal when it comes to the war on COVID-19.

SOURCE: Al Jazeera News